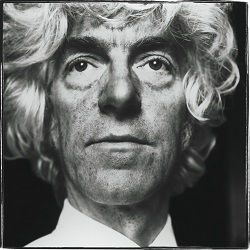

An Oxford philosopher thinks he can distill all morality into a formula. Is he right?

An Oxford philosopher thinks he can distill all morality into a formula. Is he right?

The philosopher Derek Parfit believes that neither of the people is you, but that this doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter that you have ceased to exist, because what has happened to you is quite unlike ordinary death: in your relationship to the two new people there is everything that matters in ordinary survival—a continuity of memories and dispositions that will decay and change as they usually do. Most of us care about our future because it is ours—but this most fundamental human instinct is based on a mistake, Parfit believes. Personal identity is not what matters.

Parfit is thought by many to be the most original moral philosopher in the English-speaking world. He has written two books, both of which have been called the most important works to be written in the field in more than a century—since 1874, when Henry Sidgwick’s “The Method of Ethics,” the apogee of classical utilitarianism, was published. Parfit’s first book, “Reasons and Persons,” was published in 1984, when he was forty-one, and caused a sensation. The book was dense with science-fictional thought experiments, all urging a shift toward a more impersonal, non-physical, and selfless view of human life.

Suppose that a scientist were to begin replacing your cells, one by one, with those of Greta Garbo at the age of thirty. At the beginning of the experiment, the recipient of the cells would clearly be you, and at the end it would clearly be Garbo, but what about in the middle? It seems implausible to suggest that you could draw a line between the two—that any single cell could make all the difference between you and not-you. There is, then, no answer to the question of whether or not the person is you, and yet there is no mystery involved—we know what happened. A self, it seems, is not all or nothing but the sort of thing that there can be more of or less of. When, in the process of a zygote’s cellular self-multiplication, does a person start to exist? Or when does a person, descending into dementia or coma, cease to be? There is no simple answer—it is a matter of degrees.

Parfit’s view resembles in some ways the Buddhist view of the self, a fact that was pointed out to him years ago by a professor of Oriental religions. Parfit was delighted by this discovery. He is in the business of searching for universal truths, so to find out that a figure like the Buddha, vastly removed from him by time and space, came independently to a similar conclusion—well, that was extremely reassuring. (Sometime later, he learned that “Reasons and Persons” was being memorized and chanted, along with sutras, by novice monks at a monastery in Tibet.) It is difficult to believe that there is no such thing as an all-or-nothing self—no “deep further fact” beyond the multitude of small psychological facts that make you who you are. Parfit finds that his own belief is unstable—he needs to re-convince himself. Buddha, too, thought that achieving this belief was very hard, though possible with much meditation. But, assuming that we could be convinced, how should we think about it?

Parfit has always been preoccupied with how to think about our moral responsibilities toward future people. It seems to him the most important problem we have. Besides the issue of global warming, there is the issue of population. It would seem that if the earth were teeming with many billions of people, making everyone’s life worse, that would be bad. But what if the total sum of human happiness would be higher with many billions of people whose lives were barely worth living—higher, that is, than with a smaller population of well-off people? Wouldn’t the first situation be, in some moral sense, better? Parfit calls this the Repugnant Conclusion. It seems absurd, but, at least for a consequentialist, its logic is difficult to counter.

The future makes everything more complicated, which is, apart from its enormous importance, why he likes to think about it. The first paper Parfit wrote after he began to study philosophy was on the metaphysics of time. Now this is the subject to which he plans to return. There are so many things about time that he finds puzzling.

He sees that we have the ability to make the future much better than the past, or much worse, and he knows that he will not live to discover which turns out to be the case. He knows that the way we act toward future generations will be partly determined by our beliefs about what matters in life, and whether we believe that anything matters at all. This is why he continues to try so desperately to prove that there is such a thing as moral truth.

[Disclaimer: I assert no claim of ownership of the ideas or the construction of the words (above). I read the much longer article; and of the approximate 139 paragraphs and nearly 11,000 words, I extracted but SEVEN teaser paragraphs. If any of this has tickled your curiosity at all, please visit the source publication and learn more about this fascinating, brilliant, and charmingly unusual mind and the man that conveys it from an outstanding professional writer.]

Source: How To Be Good by Larissa MacFarquhar, a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1998.