Breathe

अनति ; anati ; to breathe , to live

Breath, on the other hand, is a noun that most often means the air that is inhaled and exhaled by creatures that experience respiration. Breath is derrived from the Middle English breth and from Old English braeth.

Historically, the neurophysiology of respiration has focused on automatic brain stem processes. However, research into higher brain mechanisms underlying the cognitive aspects of breathing are gaining increasing interest. Contemporary studies that involve recordings made directly from within the brains of humans undergoing neurosurgery, indicate breathing can also change your brain.

Put another way, changes in breathing — for example, breathing at different paces or paying careful attention to the breaths — are shown to engage different parts of the brain in different ways.

And since this relationship between breath and the body/mind is a two way street, as fear shortens your breath, so can the mindful lengthening of your breath dissolve fear.

The mind changes the breath, but the breath also changes the mind.

West vs. East

Modern science; however, is bridging the gap. It now offers an account of how this works. By consciously deepening the breath, we reduce blood pressure and heart rate. We calm the nervous system and stimulate the lymphatic system’s detoxification process. We also calm the mind – shifting brainwave activity from anxiety producing beta-waves to calmer, more focused, alpha-waves.

Mindful Breathing

The breath is life, to stop breathing is to die. The breath is vital, natural, soothing, revealing. It is our constant companion. Wherever we go, at all times, the breath sustains life and provides the opportunity to develop and strengthen our mental abilities and spiritual qualities.

We learn how to relax the body and calm the mind. As the mind quiets and clears, we investigate how life, how the mind and body, unfolds. We discover the fundamental reality of human existence and learn how to live our lives in harmony with that reality. And all the while, we are anchored in the breath, nourished and sustained by the breath, soothed and balanced by the breath, sensitive to the breathing in and breathing out.

Mindful Breathing is the mental cultivation often practiced and most often taught by the Buddha Gautama.

For more than 2500 years, this practice has been preserved and passed along. It continues to be a vital part of the lives of practicing Buddhists throughout the world. The comprehensive form of Mindful Breathing leads to the realization of humanity's highest potential – enlightenment. That said, there are other (more immediate) benefits and so offers something to people at all stages of intellectual and spiritual development.

In the Pali language of ancient Buddhist text, this practice called "Anapanasati" which means "mindfulness with in-breaths and out-breaths."

Anapanasati brings us into touch with reality and nature. We often live in our heads - in ideas, dreams, memories, plans, words, and all that. So we do not have the opportunity to understand our own bodies even, never taking the time to observe them (except when the excitement of illness and sex occurs). We begin to learn what is what, what is real and what is not, what is necessary and what is unnecessary, what is conflict and what is peace.

With Anapanasati we learn to live in the present moment, the only place one can truly live. Each breath, however, is a living reality within the boundless here-now.

Lastly, as far as this brief discussion is concerned, Anapanasati helps us to ease up on and let go of the selfishness that is destroying our lives and world. Our personal relations, societies and planet are tortured by the lack of compassion and peace. The conflict, strife, struggle, and competition, all the violence and crime, the exploitation and dishonesty, arises out of our selfcentered striving, which is born out of our selfish thinking.

Anapanasati will get us to the bottom of this nasty "I-ing" and “my-ing" which spawns selfishness. There is no need to shout for peace when we merely need breath with wise awareness.

May we all realize the purpose for which we were born.

Derrivative thought originating from Santikaro Bhikkhu (1988)

Quick Start

The most basic way to do mindful breathing is simply to focus your attention on your breath, the inhale and exhale. You can do this while standing, but ideally you’ll be sitting or even lying in a comfortable position. Your eyes may be open or closed, but you may find it easier to maintain your focus if you close your eyes. It can help to set aside a designated time for this exercise, but it can also help to practice it when you’re feeling particularly stressed or anxious. Experts believe a regular practice of mindful breathing can make it easier to do it in difficult situations.

- Find a relaxed, comfortable position. You could be seated on a chair or on the floor on a cushion. Keep your back upright, but not too tight. Hands resting wherever they’re comfortable. Tongue on the roof of your mouth or wherever it’s comfortable.

- Notice and relax your body. Try to notice the shape of your body, its weight. Let yourself relax and become curious about your body seated here—the sensations it experiences, the touch, the connection with the floor or the chair. Relax any areas of tightness or tension. Just breathe.

- Tune into your breath. Feel the natural flow of breath—in, out. You don’t need to do anything to your breath. Not long, not short, just natural. Notice where you feel your breath in your body. It might be in your abdomen. It may be in your chest or throat or in your nostrils. See if you can feel the sensations of breath, one breath at a time. When one breath ends, the next breath begins.

- Now as you do this, you might notice that your mind may start to wander. You may start thinking about other things. If this happens, it is not a problem. It's very natural. Just notice that your mind has wandered. You can say “thinking” or “wandering” in your head softly. And then gently redirect your attention right back to the breathing.

- Stay here for five to seven minutes. Notice your breath, in silence. From time to time, you’ll get lost in thought, then return to your breath. After a few minutes, once again notice your body, your whole body, seated here. Let yourself relax even more deeply and then offer yourself some appreciation for doing this practice today.

Sometimes, especially when trying to calm yourself in a stressful moment, it might help to start by taking an exaggerated breath: a deep inhale through your nostrils (3 seconds), hold your breath (2 seconds), and a long exhale through your mouth (4 seconds). Otherwise, simply observe each breath without trying to adjust it; it may help to focus on the rise and fall of your chest or the sensation through your nostrils. As you do so, you may find that your mind wanders, distracted by thoughts or bodily sensations. That’s OK. Just notice that this is happening and gently bring your attention back to your breath.

Select a place with good air circulation, where you can breathe comfortably. While one can practice almost anywhere, when getting started, there should be nothing particularly exciting or disturbing in the immediate environment. Turn off or silence your electronic devices. If possible, avoid places where a television or radio is playing.

Noises which are steady and have no meaning (such as white or brown noise) may help mask out distracting sounds. Other environmental noises are no problem unless you find them to be distracting and your attention attaches to such noise. Sounds with meaning, such as people speaking, are almost always more of a problem for those just learning to practice. If you can't find a quiet place, pretend there aren't any sounds. Just be determined to practice and it will work out eventually. With practice, you'll find you can meditate anywhere.

Sit up straight (with all the vertebrae of the spine fitting together snugly). Keep your head upright.

If you want to practice with your eyes closed from the start, that's up to you. From the beginning, in my practice, I close my eyes. If you are going to keep your eyes open, do the following:

Direct your eyes towards the tip of your nose so that nothing else is seen. Whether you see it or not doesn't really matter, just gaze in its direction. Once you get used to it, the results will be better than closing the eyes, and you won't be encouraged to fall asleep so easily. In particular, people who are sleepy should practice with their eyes open rather than closed. Practice like this steadily and they will close by themselves when the time comes for them to close.

The method of starting with the eyes open gives better long-term results for most beginners. Some people, however, will feel that it's too difficult or they feel they are too easily distracted, especially those who are attached to closing their eyes. They won't be able to practice with their eyes open, and may close them if they wish.

Place your hands, palms up, in your lap, comfortably, one on top of the other. Overlap or cross your legs in a way that distributes and holds your weight well, so that you can sit comfortably and will not fall over easily. If you are sitting in a chair, do not cross your legs or ankles. Place your feet flat on the floor comfortably.

The legs can be overlapped in an ordinary way or crossed, whichever you prefer or are able to do. Some larger people have difficulty crossing their legs. Fancy postures are not necessary. Merely sit with the legs arranged so that your weight is evenly balanced and you cannot tip over easily -- that's good enough. The more difficult and serious postures can be left for when one becomes more limber and advanced in practice.

In special circumstances -- when you are sick, not feeling well, or just tired -- you can rest against something, sit on a chair, or use a deck chair, in order to recline a bit. Those who are sick can even lie down to meditate.

"Chasing After All The Time"

Feel your breath as you inhale and exhale. In your very first few practice sessions, to make it easy to recognize all aspects of your breathing, try to breathe as long and deeply as you can. Force the air in and out deliberately. Do so in order to know clearly for yourself what the breath rubs against or touches as it draws in and out along its path. In a simple way, notice where it appears to end in the belly (by taking the physical sensations as one's measure rather than anatomical reality).

Note your breathing in an easy-going way as well as you can, well enough to fix the inner and outer end points of the breathing. Don't be tense or too strict about it.

Although the eyes are gazing inattentively at the tip of the nose, you can gather your attention or awareness or sati, as it's called in our technical language, in order to catch and note your own breathing in and out. (Those who like to close their eyes will do so from here on.) Those who prefer to leave the eyes open will do so continually until the eyes gradually close on their own as concentration and calmness (samadhi) increases.

Most people will feel the breath striking at the tip of the nose and should take that point as the outer end. (In people with flat or upturned noses the breath will strike on the edge of the upper lip, and they should take that as the external end.) Now you will have both outer and inner end points by fixing one point at the tip of the nose and the other at the navel. The breath will drag itself back and forth between these two points. Here make your mind just like something which chases after or stalks the breathing, like a tiger or a spy, unwilling to part with it even for a moment, following every breath for as long as you meditate. This is the first step of our practice. We call it "chasing after (or stalking) the whole time."

Earlier we said to begin by trying to make the breathing as long as possible, and as strong, vigorous, and rough as possible, many times from the very start. Do so in order to find the end points and the track the breath follows between them. Once the mind (or sati) can catch and fix the breathing in and out -- by constantly being aware of how the breath touches and flows, then where it ends, then how it turns back either inside or outside -- you can gradually relax the breathing until it becomes normal no longer forcing or pushing it in any way. Be careful: don't force or control it at all! Still, sati fixes on the breathing the whole time, just as it did earlier with the rough and strong breathing.

Sati (meaning) is the ability to pay attention to the entire path of the breath from the inner end point (the navel or the base of the abdomen) to the outer end point (the tip of the nose or the upper lip). However fine or soft the breath becomes, sati can clearly note it all the time. If it happens that we cannot note (or feel) the breath because it is too soft or refined, then breathe more strongly or roughly again. (But not as strong or rough as before, just enough to note the breath clearly). Fix attention on the breathing again, until sati is aware of it without any gaps. Make sure it can be done well, that is, keep practicing until even the purely ordinary, unforced breathing can be securely observed. However long or short it is, know it. However heavy or light it is, know it. Know it clearly within that very awareness as sati merely holds closely to and follows the breathing back and forth the whole time you are meditating.

When you can do this, it means success in the level of preparation called "chasing after all the time."

Lack of success is due to the inability of sati (or the attention) to stay with the breathing the whole time. You don't know when it lost track. You don't know when it ran off to home, work, or play. You don't know until it's already gone. And you don't know when it went, how, why, or whatever. Once you are aware of what happened, catch the breathing again, gently bring it back to the breathing, and train until successful on this level. Do it for at least ten minutes each session, before going on to the next step.

"Waiting In Ambush At One Point"

The next step, the second level of preparation, is called "waiting (or guarding) in ambush at one point." It's best to practice this second step only after the first step can be done well, but anyone who can skip straight to the second won't be scolded. At this stage, sati (or recollection) lies in wait fixing at a particular point and stops chasing after the breathing. Note the sensation when the breathing enters the body all the way (to the navel or thereabouts) once, then let go or release it. Next, note when the breathing contacts the other end point (the tip of the nose) once more, then let go or leave it alone until it contacts the inner end point (navel) again.

Continue like this without changing anything. In moments of letting go, the mind doesn't run away to home, the fields, the office, or anywhere. This means that sati pays attention at the two end points -- both inner and outer -- and doesn't pay attention to anything between them. When you can securely go back and forth between the two end points without paying attention to things in between, leave out the inner end point and focus only on the outer, namely, the tip of the nose.

Now, sati consistently watches only at the tip of the nose.

Whether the breathing strikes while inhaling or while exhaling, know it every time. This is called "guarding the gate." There's a feeling as the breathing passes in or out; the rest of the way is left void or quiet. If you have firm awareness at the nose tip, the breathing becomes increasingly calm and quiet. Thus you can't feel movements other than at the nose tip. In the spaces when it's empty or quiet, when you can't feel anything, the mind doesn't run away to home or elsewhere. The ability to do this well is success in the "waiting in ambush at one point" level of preparation.

Lack of success is when the mind runs away without you knowing. It doesn't return to the gate as it should or, after entering the gate, it sneaks all the way inside. Both of these errors happen because the period of emptiness or quiet is incorrect and incomplete. You have not done it properly since the start of this step. Therefore, you ought to practice carefully, solidly, expertly from the very first step.

Even the beginning step, the one called "chasing after the whole time," is not easy for everyone. Yet when one can do it, the results -- both physical and mental -- are beyond expectations. So you ought to make yourself able to do it, and do it consistently, until it is a game like the sports you like to play. If you have even two minutes, by all means practice. Breathe forcefully, if your bones crack or rattle that's even better. Breathe strongly until it whistles, a little noise won't hurt. Then relax and lighten it gradually until it finds its natural level.

The ordinary breathing of most people is not natural or normal, but is coarser or lower than normal, without us being aware. Especially when we do certain activities or are in positions which are restricted, our breathing is more or less course than it ought to be, although we don't know it. So you ought to start with strong, vigorous breathing first, then let it relax until it becomes natural. In this way, you'll end up with breathing which is the "middle way" or just right. Such breathing makes the body natural, normal, and healthy. And it is fit for use as the object of meditation at the beginning of anapanasati. Let us stress once more that this first step of preparation ought to be practiced until it's just a natural game for every one of us, and in all circumstances. This will bring numerous physical and mental benefits.

Actually, the difference between "chasing after the whole time" and "waiting in ambush at one place" is not so great. The latter is a little more relaxed and subtle, that is, the area noted by sati decreases. To make this easier to understand, we'll use the simile of the baby sitter rocking the baby's hammock. At first, when the child has just been put intp the hammock, it isn't sleepy yet and will try to get out. At this stage, the baby sitter must watch the hammock carefully. As it swings from side to side, her head must turn from left to right so that the child won't be out of sight for a moment. Once the baby begins to get sleepy and doesn't try to get out anymore, the baby sitter need not turn her head from left to right, back and forth, as the hammock swings. The baby sitter only watches when the hammock passes in front of her face, which is good enough. Watching only at one point while the hammock is in front of her face, the baby won't have a chance to get out of the hammock just the same, because the child is ready to fall sleep (Although the baby will fall asleep, the meditator should not!).

The first stage of preparation in noting the breathing -- "chasing after the whole time" -- is like when the baby sitter must turn her head from side to side with the swinging hammock so that it isn't out of sight for a moment. The second stage where the breathing is noted at the nose tip -- "waiting and watching at one point" -- is like when the baby is ready to sleep and the baby sitter watches the hammock only when it passes her face.

When you have practiced and trained fully in the second step, you can train further by making the area noted by sati even more subtle and gentle until there is secure, stable concentration. Then concentration can be deepened step by step until attaining one of the jhanas, which, for most people, is beyond the rather easy concentration of the first steps.

The jhanas are a refined and precise subject with strict requirements and subtle principles. One must be strongly interested and committed for that level of practice. At this stage, just be constantly interested in the basic steps until they become familiar and ordinary. Then you might be able gather in the higher levels later.

May ordinary lay people give themselves the chance to meditate in a way which has many benefits both physically and mentally, and which satisfies the basic needs of our practice, before going on to more difficult things. May you train with these first steps in order to be fully equipped with sila (morality), samadhi (concentration), and panna (wisdom), that is, to be fully grounded in the noble eightfold path. Even if only a start, this is better than not going anywhere.

Your body will become more healthy and peaceful than usual by training in successively higher levels of samadhi. You will discover something that everyone should find in order to not waste the opportunity of having been born.

Source:

Copyright © Mindful Awareness Research Center (MARC) UCLA

Shared without permission (website is not https enabled).

www.marc.ucla.edu 310.206.7503 marcinfo@ucla.edu

Mindfulness of Breath Discourse

The Ānāpānasati Sutta (Pāli) or Ānāpānasmṛti Sūtra (Sanskrit), "Breath-Mindfulness Discourse," is a discourse that details the Buddha's instruction on using awareness of the breath (anapana) as an initial focus for meditation. The sutta includes sixteen steps of practice, and groups them into four tetrads, associating them with the four satipatthanas (placings of mindfulness). According to Thanissaro Bhikkhu, this sutta contains the most detailed meditation instructions in the Pali Canon.

Presented first (below) is a four-part lecture series where Bhikkhu Bodhi leads an in-depth examination of MN 118, the Anapanasati Sutta. This is one of the most thorough audio treatments presently available. It is worth noting that these four recordings are but a small part of a very much larger exploration of the entire Majjhima Nikaya.

Majjhima Nikaya 118 - Part 1

Majjhima Nikaya 118 - Part 2

Majjhima Nikaya 118 - Part 3

Majjhima Nikaya 118 - Part 4

Additional Talks

The treatment above is very thorough, but for some, it is overwhelming. Below are three shorter treatments of the same material.

Ajahn Brahmali

Bhante Vimalaramsi (audio)

Bhikkhu Bodhi

And finally, the last two lectures are presented by Ajahn Brahm, they similar in nature to the three above. What makes these last two most interesting is that they are ten years apart. The message isn't particularly different, but the messenger has a decade of wisdom and experience between the two tellings. While it is very subtle, I still find it interesting.

Ajahn Brahm - Mindfulness of Breathing - (2004)

Ajahn Brahm - Mindfulness of Breathing - (2014)

The Process of Physical Breathing

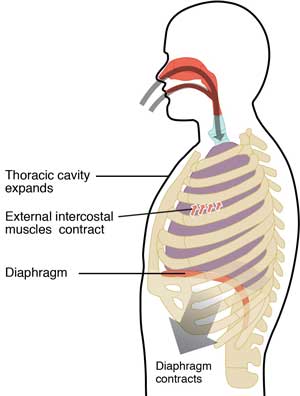

Pulmonary ventilation is the physical act of breathing. It is a process, described as the movement of air into and out of the lungs, which is driven by pressure differences between the lungs and the atmosphere. The major mechanisms that drive pulmonary ventilation are atmospheric pressure; alveolar pressure; intrapleural pressure.

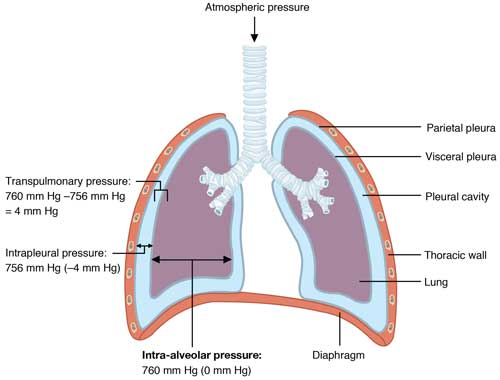

Atmospheric pressure (Patm) is the force exerted by gases present in the atmosphere. The force exerted by gases within the alveoli is called alveolar pressure1 (Palv), whereas the force exerted by gases in the pleural cavity is called intrapleural pressure (Pip). Typically, intrapleural pressure is lower, or negative to, intra-alveolar pressure. The difference in pressure between intrapleural and intra-alveolar pressures is called transpulmonary pressure. In addition, intra-alveolar pressure will equalize with the atmospheric pressure.

Pressure is determined by the volume of the space occupied by a gas and is influenced by resistance. Air flows when a pressure gradient is created, from a space of higher pressure to a space of lower pressure. Boyle’s law describes the relationship between volume and pressure. A gas is at lower pressure in a larger volume because the gas molecules have more space to in which to move. The same quantity of gas in a smaller volume results in gas molecules crowding together, producing increased pressure.

Resistance is created by inelastic surfaces, as well as the diameter of the airways. Resistance reduces the flow of gases. The surface tension of the alveoli also influences pressure, as it opposes the expansion of the alveoli. However, pulmonary surfactant helps to reduce the surface tension so that the alveoli do not collapse during expiration. The ability of the lungs to stretch, called lung compliance, also plays a role in gas flow. The more the lungs can stretch, the greater the potential volume of the lungs. The greater the volume of the lungs, the lower the air pressure within the lungs.

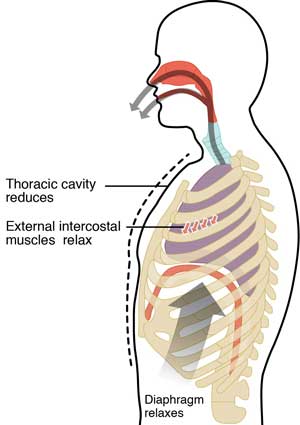

Pulmonary ventilation consists of the process of inspiration (or inhalation), where air enters the lungs, and expiration (or exhalation), where air leaves the lungs.

1 alveolar pressure is also known as inter-alveolar pressure and/or intrapulmonary pressure

Sources:

The Process of Breathing by Rice University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Craig Freudenrich, Ph.D. "How Your Lungs Work" 6 October 2000. HowStuffWorks.com. <https://health.howstuffworks.com/human-body/systems/respiratory/lung.htm> 1 April 2018

The interpulmonary pressure rises above atmospheric pressure, creating a pressure gradient that causes air to leave the lungs. However, during forced exhalation, the internal intercostals and abdominal muscles may be involved in forcing air out of the lungs.

The interpulmonary pressure rises above atmospheric pressure, creating a pressure gradient that causes air to leave the lungs. However, during forced exhalation, the internal intercostals and abdominal muscles may be involved in forcing air out of the lungs.