In the shadowy realm of horror literature, few authors have been as influential in their craft as the late Howard Phillips Lovecraft, and his lesser-known work, "The Tree," is a testament to his unique style and narrative. In the eldritch language and tone of Lovecraft, this review aims to dissect and appreciate the shadowed brilliance of "The Tree."

In the shadowy realm of horror literature, few authors have been as influential in their craft as the late Howard Phillips Lovecraft, and his lesser-known work, "The Tree," is a testament to his unique style and narrative. In the eldritch language and tone of Lovecraft, this review aims to dissect and appreciate the shadowed brilliance of "The Tree."

In the darkened valleys of the human psyche, Lovecraft weaves a tale of unnatural growth and unexplained vengeance. Situated on the craggy inclines of Mount Maenalus in Arcadia, Greece, the narrative focuses on two sculptors, Kalos and Musides, renowned for their artistic prowess. It is a tale of their companionship, rivalry, and the inscrutable workings of nature.

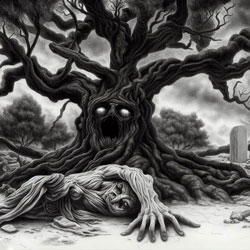

When Kalos, the more spiritual of the duo, is claimed by death, an olive tree sprouts near his grave, growing at an alarming rate, its form a grotesque mockery of life. This tree, the central figure of the tale, is an embodiment of Lovecraft's lingering horror, a symbol of the uncanny and the unknown, a harbinger of death and destruction. The narrative builds with an escalating sense of dread, reaching its climax with a storm that brings a grim resolution.

In its core, "The Tree" is a departure from Lovecraft's usual cosmic horror, focusing on the earthly and the natural. Yet it retains his signature elements: the unseen and the unknowable, the creeping dread, the unease that lingers long after the tale has ended.

The prose is intricately crafted, with Lovecraft's customary attention to detail. Lovecraft's language is a crucial aspect of his work. He crafts sentences that are vast and ornate, imbued with a sense of the archaic that adds a layer of richness to his narratives. In "The Tree," this verbose style provides an evocative portrayal of the landscape, the grotesque tree, and the chilling finale.

Notably, "The Tree" lacks the overt presence of the alien and the monstrous that pervades many of Lovecraft's works. There are no eldritch abominations or ancient deities here. Instead, it employs the subtler horror of the natural world, driven by an unseen force that defies comprehension. The story taps into the primal fear of the unknown and the inexplicable, a theme that Lovecraft has always excelled at.

Critically, "The Tree" offers much to dissect. The tale's titular entity, the olive tree, is an uncanny symbol of death and transformation. The story's ending, where the tree seemingly fulfills the dying wish of Kalos, is open to various interpretations. It can be seen as a manifestation of Kalos' will, or perhaps, the natural world's inscrutable methods.

Comparatively, "The Tree" stands as an intriguing outlier within Lovecraft's body of work. It lacks the cosmic scope of tales like "At the Mountains of Madness" or "The Call of Cthulhu," focusing instead on a localized, more intimate horror. Yet, it retains Lovecraft's signature elements and themes, making it a fascinating study of his range as a writer.

Scholars like S.T. Joshi have recognized the enduring impact of Lovecraft's work, and "The Tree" is no exception. Though it may not be his most famous story, it encapsulates his ability to evoke a sense of creeping dread and fascination with the unknown.

In conclusion, "The Tree" is a testament to Lovecraft's prowess as a writer and his unique approach to horror. It is a chilling tale of unseen forces and earthly horror, rendered in his signature verbose and evocative style. Even in its divergence from his usual themes, it showcases the essence of Lovecraftian horror and reaffirms his status as a master of the genre.

"The Tree" is a testament to Lovecraft's uncanny ability to find horror in the mundane, to weave tales of dread from the fabric of the natural world. The olive tree's grotesque growth and its seeming vengeance upon Musides strike a chord of primal fear, a testament to the power of the unknown and the inexplicable. The storm that brings the narrative to its chilling conclusion serves as a stark reminder of nature's inscrutable power and indifference, themes that resonate across Lovecraft's canon.

This tale, like much of Lovecraft's work, lingers in the mind, a haunting echo of dread and fascination. The narrative's enduring impact, the lingering horror it induces, attests to Lovecraft's mastery of his craft. Even in its divergence from his more well-known cosmic horror, "The Tree" exemplifies Lovecraft's power as a storyteller and his unique approach to the horror genre.

In comparison to the broader spectrum of Lovecraft's writings, "The Tree" provides an intriguing contrast. It eschews the cosmic and the alien, focusing instead on the earthly and the natural. Yet, it is no less potent in its horror. The story showcases Lovecraft's versatility as a writer, his ability to evoke fear and dread from a variety of sources. It is a testament to his narrative prowess, his ability to craft tales that linger in the mind long after the final word has been read.

Lovecraft's work has been the subject of extensive scholarly analysis, with researchers like Leslie S. Klinger, and Robert M. Price providing valuable insights into his style and themes. Their works underscore Lovecraft's enduring impact on horror literature and his unique approach to storytelling.

In closing, "The Tree" stands as a testament to Lovecraft's enduring literary prowess. Its subtle yet powerful horror, its focus on the unknown and the inexplicable, and its evocative prose make it a fascinating addition to his canon. Even in its divergence from his usual themes, it is undeniably Lovecraftian, a chilling tale of earthly horror that lingers in the mind long after the story has ended.

Bibliography:

- Joshi, S.T. "H.P. Lovecraft: The Decline of the West." Wildside Press LLC, 1990.

- Klinger, Leslie S. "The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft." Liveright Publishing, 2014.

- Price, Robert M. "The Philosophy of H.P. Lovecraft: The Route to Horror." New Falcon Publications, 1991.

- Harman, Graham. "Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy." Zero Books, 2012.

- Houellebecq, Michel. "H.P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life." Believer Books, 2005.

Note: The works of H.P. Lovecraft are in the public domain.

The Tree

By H. P. Lovecraft

“Fata viam invenient.”

On a verdant slope of Mount Maenalus, in Arcadia, there stands an olive grove about the ruins of a villa. Close by is a tomb, once beautiful with the sublimest sculptures, but now fallen into as great decay as the house. At one end of that tomb, its curious roots displacing the time-stained blocks of Pentelic marble, grows an unnaturally large olive tree of oddly repellent shape; so like to some grotesque man, or death-distorted body of a man, that the country folk fear to pass it at night when the moon shines faintly through the crooked boughs. Mount Maenalus is a chosen haunt of dreaded Pan, whose queer companions are many, and simple swains believe that the tree must have some hideous kinship to these weird Panisci; but an old bee-keeper who lives in the neighbouring cottage told me a different story.

Many years ago, when the hillside villa was new and resplendent, there dwelt within it the two sculptors Kalos and Musides. From Lydia to Neapolis the beauty of their work was praised, and none dared say that the one excelled the other in skill. The Hermes of Kalos stood in a marble shrine in Corinth, and the Pallas of Musides surmounted a pillar in Athens, near the Parthenon. All men paid homage to Kalos and Musides, and marvelled that no shadow of artistic jealousy cooled the warmth of their brotherly friendship.

But though Kalos and Musides dwelt in unbroken harmony, their natures were not alike. Whilst Musides revelled by night amidst the urban gaieties of Tegea, Kalos would remain at home; stealing away from the sight of his slaves into the cool recesses of the olive grove. There he would meditate upon the visions that filled his mind, and there devise the forms of beauty which later became immortal in breathing marble. Idle folk, indeed, said that Kalos conversed with the spirits of the grove, and that his statues were but images of the fauns and dryads he met there—for he patterned his work after no living model.

So famous were Kalos and Musides, that none wondered when the Tyrant of Syracuse sent to them deputies to speak of the costly statue of Tyché which he had planned for his city. Of great size and cunning workmanship must the statue be, for it was to form a wonder of nations and a goal of travellers. Exalted beyond thought would be he whose work should gain acceptance, and for this honour Kalos and Musides were invited to compete. Their brotherly love was well known, and the crafty Tyrant surmised that each, instead of concealing his work from the other, would offer aid and advice; this charity producing two images of unheard-of beauty, the lovelier of which would eclipse even the dreams of poets.

With joy the sculptors hailed the Tyrant’s offer, so that in the days that followed their slaves heard the ceaseless blows of chisels. Not from each other did Kalos and Musides conceal their work, but the sight was for them alone. Saving theirs, no eyes beheld the two divine figures released by skilful blows from the rough blocks that had imprisoned them since the world began.

At night, as of yore, Musides sought the banquet halls of Tegea whilst Kalos wandered alone in the olive grove. But as time passed, men observed a want of gaiety in the once sparkling Musides. It was strange, they said amongst themselves, that depression should thus seize one with so great a chance to win art’s loftiest reward. Many months passed, yet in the sour face of Musides came nothing of the sharp expectancy which the situation should arouse.

Then one day Musides spoke of the illness of Kalos, after which none marvelled again at his sadness, since the sculptors’ attachment was known to be deep and sacred. Subsequently many went to visit Kalos, and indeed noticed the pallor of his face; but there was about him a happy serenity which made his glance more magical than the glance of Musides—who was clearly distracted with anxiety, and who pushed aside all the slaves in his eagerness to feed and wait upon his friend with his own hands. Hidden behind heavy curtains stood the two unfinished figures of Tyché, little touched of late by the sick man and his faithful attendant.

As Kalos grew inexplicably weaker and weaker despite the ministrations of puzzled physicians and of his assiduous friend, he desired to be carried often to the grove which he so loved. There he would ask to be left alone, as if wishing to speak with unseen things. Musides ever granted his requests, though his eyes filled with visible tears at the thought that Kalos should care more for the fauns and the dryads than for him. At last the end drew near, and Kalos discoursed of things beyond this life. Musides, weeping, promised him a sepulchre more lovely than the tomb of Mausolus; but Kalos bade him speak no more of marble glories. Only one wish now haunted the mind of the dying man; that twigs from certain olive trees in the grove be buried by his resting-place—close to his head. And one night, sitting alone in the darkness of the olive grove, Kalos died.

Beautiful beyond words was the marble sepulchre which stricken Musides carved for his beloved friend. None but Kalos himself could have fashioned such bas-reliefs, wherein were displayed all the splendours of Elysium. Nor did Musides fail to bury close to Kalos’ head the olive twigs from the grove.

As the first violence of Musides’ grief gave place to resignation, he laboured with diligence upon his figure of Tyché. All honour was now his, since the Tyrant of Syracuse would have the work of none save him or Kalos. His task proved a vent for his emotion, and he toiled more steadily each day, shunning the gaieties he once had relished. Meanwhile his evenings were spent beside the tomb of his friend, where a young olive tree had sprung up near the sleeper’s head. So swift was the growth of this tree, and so strange was its form, that all who beheld it exclaimed in surprise; and Musides seemed at once fascinated and repelled.

Three years after the death of Kalos, Musides despatched a messenger to the Tyrant, and it was whispered in the agora at Tegea that the mighty statue was finished. By this time the tree by the tomb had attained amazing proportions, exceeding all other trees of its kind, and sending out a singularly heavy branch above the apartment in which Musides laboured. As many visitors came to view the prodigious tree, as to admire the art of the sculptor, so that Musides was seldom alone. But he did not mind his multitude of guests; indeed, he seemed to dread being alone now that his absorbing work was done. The bleak mountain wind, sighing through the olive grove and the tomb-tree, had an uncanny way of forming vaguely articulate sounds.

The sky was dark on the evening that the Tyrant’s emissaries came to Tegea. It was definitely known that they had come to bear away the great image of Tyché and bring eternal honour to Musides, so their reception by the proxenoi was of great warmth. As the night wore on, a violent storm of wind broke over the crest of Maenalus, and the men from far Syracuse were glad that they rested snugly in the town. They talked of their illustrious Tyrant, and of the splendour of his capital; and exulted in the glory of the statue which Musides had wrought for him. And then the men of Tegea spoke of the goodness of Musides, and of his heavy grief for his friend; and how not even the coming laurels of art could console him in the absence of Kalos, who might have worn those laurels instead. Of the tree which grew by the tomb, near the head of Kalos, they also spoke. The wind shrieked more horribly, and both the Syracusans and the Arcadians prayed to Aiolos.

In the sunshine of the morning the proxenoi led the Tyrant’s messengers up the slope to the abode of the sculptor, but the night-wind had done strange things. Slaves’ cries ascended from a scene of desolation, and no more amidst the olive grove rose the gleaming colonnades of that vast hall wherein Musides had dreamed and toiled. Lone and shaken mourned the humble courts and the lower walls, for upon the sumptuous greater peristyle had fallen squarely the heavy overhanging bough of the strange new tree, reducing the stately poem in marble with odd completeness to a mound of unsightly ruins. Strangers and Tegeans stood aghast, looking from the wreckage to the great, sinister tree whose aspect was so weirdly human and whose roots reached so queerly into the sculptured sepulchre of Kalos. And their fear and dismay increased when they searched the fallen apartment; for of the gentle Musides, and of the marvellously fashioned image of Tyché, no trace could be discovered. Amidst such stupendous ruin only chaos dwelt, and the representatives of two cities left disappointed; Syracusans that they had no statue to bear home, Tegeans that they had no artist to crown. However, the Syracusans obtained after a while a very splendid statue in Athens, and the Tegeans consoled themselves by erecting in the agora a marble temple commemorating the gifts, virtues, and brotherly piety of Musides.

But the olive grove still stands, as does the tree growing out of the tomb of Kalos, and the old bee-keeper told me that sometimes the boughs whisper to one another in the night-wind, saying over and over again, “Οἶδα! Οἶδα!—I know! I know!”